Trump’s Plan for 100% Tariff on Computer Chips

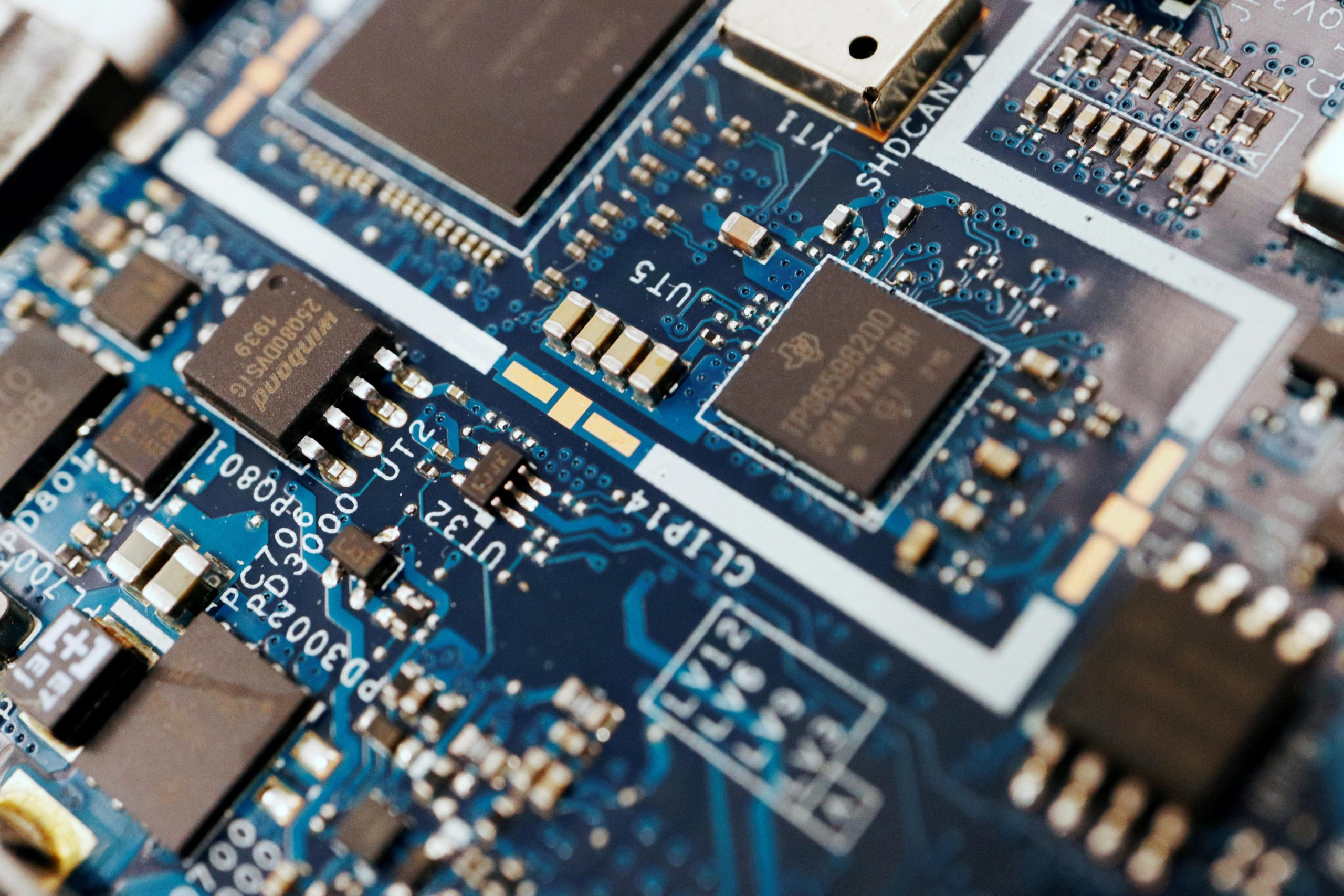

President Donald Trump has proposed a 100% tariff on imported computer chips, a policy that could have significant implications for businesses and consumers alike. Experts warn that this move may force companies to reduce production or increase prices, as the cost of importing chips would rise sharply.

The details of the tariff remain unclear, and while the inflationary impact might not be as severe as other tariffs, it could still affect a wide range of products. These include smartphones, laptops, cars, and video game consoles. Zac Rogers, an associate professor of operations and supply chain management at Colorado State University, emphasized how deeply integrated computer chips are in everyday life.

“Almost everything you use today involves at least 100 chips,” Rogers said. “This tariff could have far-reaching consequences.”

How Will the Tariff Work?

Trump introduced the new tariff during an Oval Office event on August 6, mentioning that companies committed to producing chips within the United States would be exempt. However, many aspects of the policy remain undefined. For example, it is not yet clear when the tariff will take effect or how it will affect products containing chips like laptops.

Jason Miller, a professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University, noted that without specific details on which products will be affected, it’s difficult to assess the full impact.

“The exact harmonized system codes covered by the tariff are crucial,” Miller said. “Until we see those, we can’t fully understand the implications.”

U.S. Semiconductor Production and Imports

The United States already produces a considerable amount of semiconductors, exporting around $58 billion worth annually, according to Census Bureau data. However, Miller pointed out that the U.S. excels in producing high-end chips, while lower-end chips—often found in household appliances—are typically imported from countries like Malaysia. High-end chips, such as those used in advanced technology, are often sourced from Taiwan.

In total, the U.S. imports roughly $60 billion in semiconductors each year. Miller explained that it doesn’t make economic sense for the U.S. to produce all types of chips domestically, as resources should be focused on where the country has a competitive advantage.

Impact on Prices and Consumer Costs

Experts suggest that the new chip tariff may not hit manufacturers as hard as previous tariffs, such as the 50% tax on steel and aluminum or the 25% auto tariffs. However, it could add pressure to companies already dealing with rising import costs.

John Mitchell, president and CEO of the Global Electronics Association, warned that the tariff could lead to higher prices for goods like laptops, appliances, vehicles, and medical devices. He also mentioned that over 60% of member companies have reported increased costs and production delays due to past tariffs.

For certain products, like cars, chips make up only a small portion of the overall cost. However, Ivan Drury, director of insights at Edmunds, described the tariff as another challenge for automakers, who are already facing a 25% auto tariff.

Automakers like General Motors and Stellantis have already felt the financial impact of tariffs, with GM reporting over $1 billion in costs and Stellantis expecting about $1.7 billion in losses this year. Drury noted that while automakers haven’t passed these costs onto consumers yet, this situation may not last forever.

Potential for Shortages

Another concern is the possibility of product shortages. The U.S. experienced a major semiconductor shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting the availability of cars, laptops, and gaming consoles. While the new tariff isn’t expected to cause widespread shortages, some companies may reduce production if import costs rise significantly.

Stellantis has already paused production at some plants to avoid paying tariffs, leading to a 6% year-over-year decline in car shipments. Rogers warned that while the situation may not be as severe as the 2021 shortage, consumers may end up paying more for the same products.

“It may not be as bad as 2021, but we’ll just have to pay more for them,” Rogers said. “If we pay more, we buy less.”